UN0474756BW

Mental health – it’s time to change the narrative

Home

Stories

Mental health – it’s time to change the narrative

Breaking the silence surrounding mental illness.

24-year-old Ezekiel Raui chuckles. He is refreshingly proud of his low Instagram following.

860 followers is surprisingly low for someone who has been recognised by the Queen, invited for a kōrero (discussion) at the White House Tribal Leaders Gathering hosted by the Obama's and recently earned a top enterprise award.

Ezekiel, or Zeek, to his friends and whānau, is of Te Rarawa and Cook Islands descent and has dedicated his life to addressing mental health and wellbeing, developing the youth suicide prevention programme Tū Kotahi – to stand tall.

Now Ezekiel is standing behind UNICEF’s latest flagship global report – The State of the World’s Children – which focuses on mental health and explores how risk and protective factors in the home, school and community shape mental health outcomes for children and adolescents.

Launched in Paris on 5 October, the 151-page report estimates that economies stand to lose NZD$560 billion a year due to mental disorders among young people. More than 1 in 7 aged 10–19 is estimated to live with a diagnosed mental disorder globally, and almost 46,000 adolescents die from suicide each year.

New Zealand is highlighted in the report as suicide and depression have been linked to experiences of racial discrimination among Māori. Indigenous groups around the world also face discrimination-based risks to mental health.

The trauma of suicide can travel beyond the victim’s own family to affect friends, schoolmates and communities. These ripples can, in turn, lead to the loss of other young lives and clusters of suicide and suicidal behaviour are more common among young people than among adults.

Ezekiel's community lost five young people to suicide in less than three months. Growing up in the far north in Taipa, Ezekiel says there weren’t many positive connotations for Māori and Pacific youth.

“There were a lot of negative stereotypes and people telling us that we were never going to make it. Words can wear you down and if your environment is facing challenges and those challenges are prolonged, then it can be quite easy to fall into that mentality.”

“When a friend died outside of Taipa, I realized that the struggles were not just confined to our community. Losing friends to suicide sparked a conversation and we were sharing some pretty tough stuff with each other. To be honest, we didn’t know what to do with it.” Ezekiel and his peers went on to develop Tū Kotahi , a national whole-school youth suicide prevention programme, with the goal of providing a clear and safe pathway and pipeline for young people to support each other.

“When a young person confides in their peer and says don't tell anyone, it’s a challenging situation to navigate. Through Tū Kotahi young people can access the tools and knowledge they need to discuss mental health issues and whakamomori (suicide), and learn how to get their friends safely to support.”

According to UNICEF’s report, protective factors such as loving caregivers, safe school environments, and positive peer relationships can help reduce the risk of mental disorders.

“When I think about the impacts of mental health on the community or the way in which our community reacted to the loss of the young people’s lives, it highlighted the importance of whānau, family, and the importance of community and education,” says Ezekiel.

At Taipa Area School, a Year 1 to 15 school with just 300 pupils, Ezekiel says two teachers in particular became his tuakana teina role models for sharing experience and knowledge. “Mrs Timmer-Arends was our maths teacher. She taught us Dutch and in exchange we supported her te reo Māori. Although I struggled with the subject, she made maths interesting – teaching angles by shooting basketball hoops. As a bonus, she fed us and made sure we had enough numeracy credits to get into university.”

Ezekiel and six fellow students were also eager to learn business studies at school. “We wanted to be rich. We wanted to be millionaires!!” laughs Ezekiel.

Unfortunately, there wasn’t a business studies teacher until Miss Berghan put her hand up to learn alongside the students.

“Miss Berghan had never taught business before, but she studied with us and made learning possible. We were lucky to have teachers who put in extra effort, so we didn’t become the stereotypes. They wanted us to succeed.”

The report states that while schools can be healthy and inclusive environments, they can also be places where children experience bullying.

KiVA, a research and evidence-based programme has the goal of preventing bullying, a known risk for mental health conditions. Researchers estimated that the long-term return on investment is NZD $7.52 for every NZD $1 invested.

Bullying, however, is not limited to the classroom or playgrounds. Ezekiel says too often New Zealanders are taking potshots at those who are doing their best to improve mental health outcomes.

“Finger pointing is prominent in mental health. Everyone is good at placing blame but if we continue to bully and blame government departments, then our stats are only going to move in the wrong direction. We can hold people to account without diminishing their mana – their integrity.”

We can’t teach our young people anti-bullying behaviour, if we don’t lead by example. According to UNICEF’s report, mental health, like physical health, should be thought of as a positive, yet far too many children and adolescents struggle in silence, stifled by misunderstanding and stigma.

Ezekiel says that mental health has sometimes been a political football in New Zealand and because it is a familiar term, it is immediately associated with a deficit point of view without balanced messaging.

“Overwhelmingly, articles written about mental health are negative and over the past decade that perception has been further ingrained and people may be less likely to open up. It’s important to highlight positive mental health as well.”

Mental health underlies the human capacity to think, feel, learn, work, build meaningful relationships and contribute to communities and the world. It is an intrinsic part of individual health and a foundation for healthy communities and nations. Who does Ezekiel admire for their contribution to address mental health in Aotearoa New Zealand?

Ezekiel is excited. There are too many options for him to choose and he happily rattles them off.

“There are the stalwarts of Māori mental health; Sir Mason Durie, Dr Meihana Durie, Dr Maria Baker, Michael Naera and so many iwi around Aotearoa who have been at the forefront of leading mental health discussions.”

“There’s also amazingly talented and dedicated people driving positive change like V.O.H Co-Founders Jazz Thornton and Genevieve Mora, Talei Bryant, and the Soften Up Bro duo John Kingi and Heemi Kapa-Kingi, John Kirwan, Mike King, Te Hiringa Hauora/Health Promotion Agency and The New Zealand Ministry of Health.”

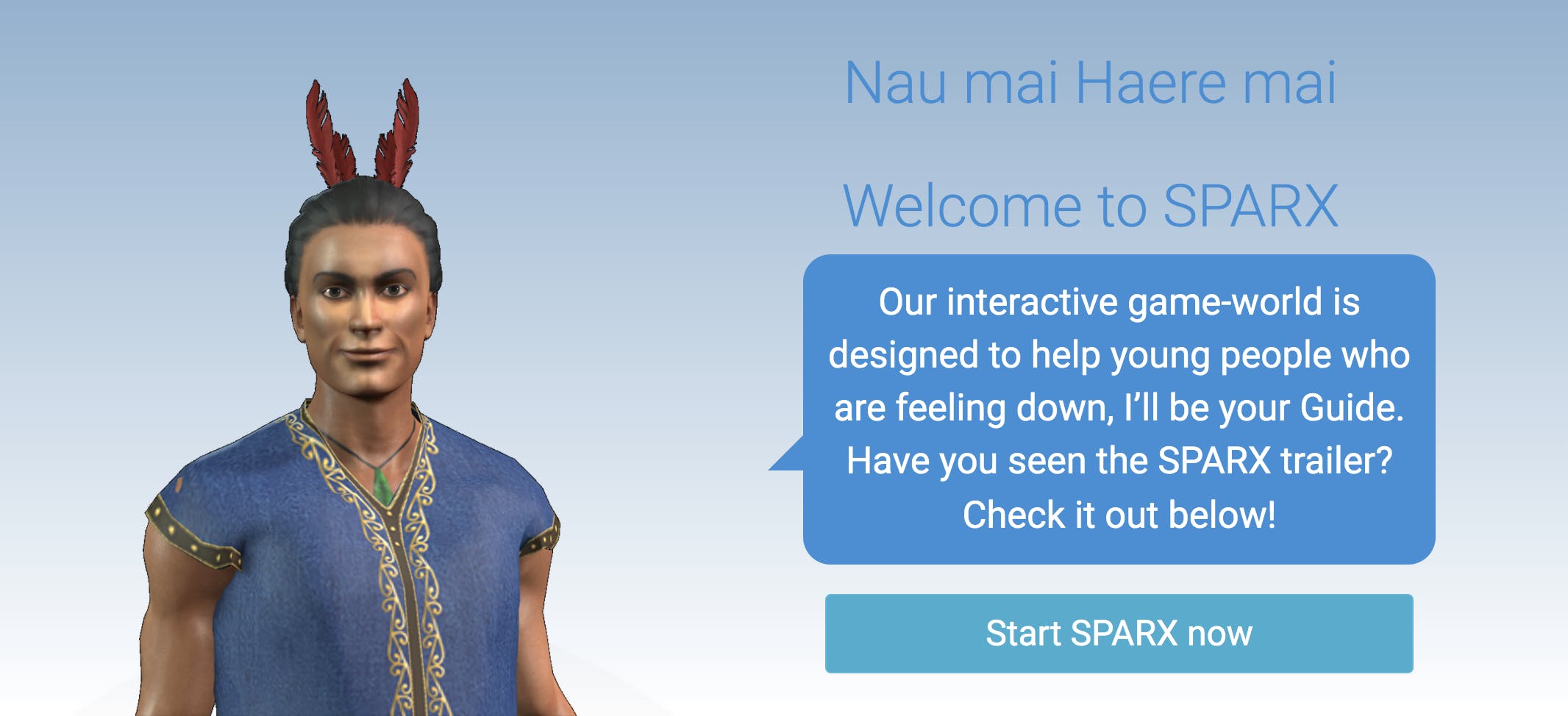

UNICEF’s report highlights the positive role that digital technologies can play to support mental health and psychosocial support and credits SPARX, a computer game developed in New Zealand and funded by the New Zealand Ministry of Health, with finding an innovative solution to help young people with depression, anxiety or stress.

Ezekiel has an ambitious goal, one he knows others share too – to see New Zealand hit the zero mark.

“As I’ve worked in mental health and been a part of this amazing kaupapa, discussion, one goal that I carry with me is to make myself redundant when there are no suicides. When our service is no longer needed because people have the tools and knowledge to protect themselves, then I think we will have completed what we set out to do.”

Ezekiel says UNICEF’s report is a reaffirmation that the data is relevant and highlights why so many people are putting in the blood, sweat, and tears to get programmes underway and initiatives on the table.

There is a question Ezekiel is suddenly struggling with – who has he influenced?

Ezekiel pauses for the first time in the interview. He doesn’t have an answer immediately, or still 30 seconds later. Maybe when you’re living and breathing mental health, it’s easier to identify the work ahead than recognise the moments of success.

Finally, Ezekiel remembers a young boy.

“After traveling to the White House and meeting former US President Barack Obama and Michelle Obama, I was asked to give a talk at a school in the South Island. A ten-year-old Māori boy listened to my talk and afterwards he told me that his dream was to be a pilot. By chance, I had been given me a book about the stages of wind and aviation, so I gave it to him.”

Ezekiel pauses. He’s struggling to now recall what year we are in. “Lockdown has messed everything up, what year are we in?!” Ezekiel laughs before continuing.

“Before lockdown, I ran into the boy again. He told me that he hadn’t felt cool to be Māori but when I gave him the book, he felt like he could chase his dreams. Now he is about to finish high school and plans to study aviation.”

“It was a grounding moment. The accolades have provided a great platform for me, but it’s moments like that are a reminder that you’re doing the right thing in life. It took me back to when I was young and when I saw inspirational people who I wanted to be.” Ezekiel is no longer at a loss for words.

“We have to kick open the door, as opposed to just opening it. We have to break down the barriers around mental health. I want young people to have tangible proof that it’s possible to have good mental health and be proud of it.”

It’s time to change the narrative.

“Hey, today my mental health is really good,” says Ezekiel proudly.